The Nero Conspiracy Theory

A chapter from "Rome and Jerusalem." Conspiracy theories have been with us forever.

8/10/20255 min read

This is strangely resonant today: Nero was flamboyant and amoral, and his rule was erratic and harmful. For this, the elites hated him, but the public loved him and missed him when he was gone.

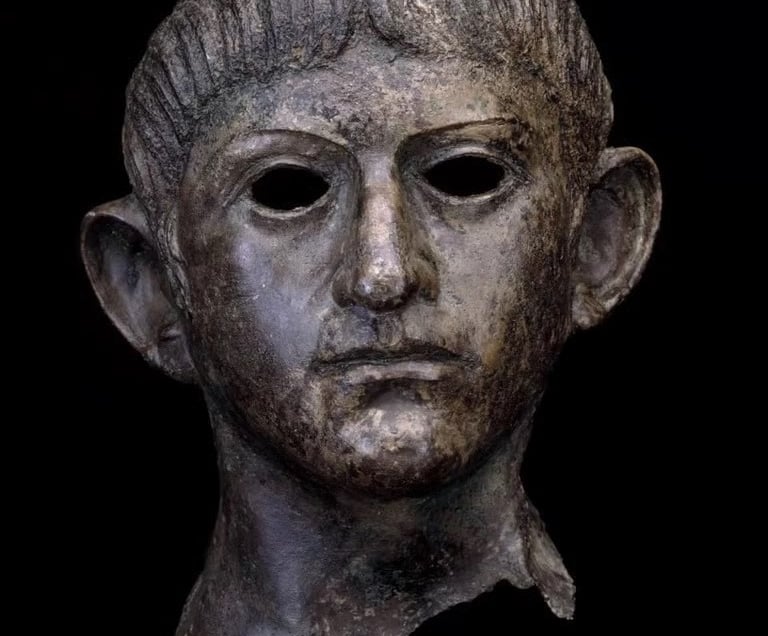

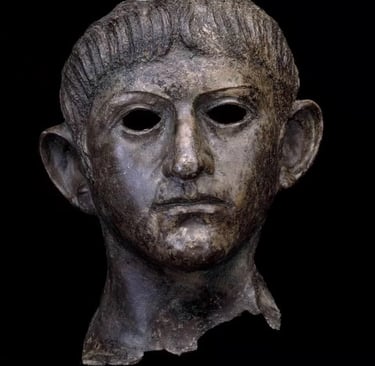

Did Emperor Nero really die? Did he really commit suicide by stabbing himself in the throat? Were those really his ashes in the grand porphyry sarcophagus in the Domitians’ tomb at the foot of the Garden Hill, just outside the city walls?

Several months had passed since the events of early June 68, and almost everyone in the capital was asking themselves such questions. And—incredibly—many answered them in the negative. For whatever reason, many in Rome did not want to believe that Nero had died. They said: our lord lives, bides his time, and will soon return!

The rumor was that Nero, with the help of a few trusted freedmen, had staged his suicide, cremated a substitute corpse, and escaped; and that he did so to confuse the assassins sent to kill him. Of course, he had had to act that way—he had had no choice—because everyone had abandoned him: some out of fear, others from stupidity. But he escaped and was hiding somewhere in Italy. Or overseas. And he was waiting for an opportune moment to return. But he would return and reassume the reins of power.

And soon! For neither Rome nor the provinces were going to endure the abomination of the government of senile Galba. As someone rightly said about him: “he might be fit to rule, except last time he looked, he discovered he ruled already.”

Others yet refused to believe the story of Nero’s suicide on other grounds, saying:

“Nero was a coward. There is no way he would have killed himself. And since no one boasts about having killed him and no one demands the bounty on his head, perhaps Nero is not dead after all?”

Finally, the suspicious asked:

“Who has seen the cremation of Nero and the placement of his ashes in the tomb of the Domitians?” (The Domitians’ tomb was the emperor’s family tomb.) “How odd and how very suspicious!” they said. “All the supposed witnesses had been women: his two nurses, Ecloge and Alexandra, and Acte, a concubine he had rejected many years ago but who still loved him. The women spared no expense to make the funeral as dignified as possible. They spent over 200,000 sesterces. Acte probably paid most of it, as she was an extremely wealthy woman thanks to Nero’s favor: she had extensive estates, magnificent villas, and swarms of servants. The three women cremated a body and collected its ashes in a snow-white cloth with gold thread—the cloak Nero had worn at the New Year’s celebrations six months earlier. But whose body was it? Was it really Nero’s? Only they knew—and they knew because Nero had trusted them. Could it be that they spent all that money on the funeral in order to give the false impression that the body of the emperor was being buried while he himself was, in fact, hiding somewhere else?”

Sporus had also stood by the burning pyre. Once upon a time, Nero had decided to make a girl of him. He had him castrated and then married him, formally and ceremonially, as his wife (in Greece, of course, as Rome would never have stood for such goings on). Later, the boy-girl was present at the scene of the suicide. All this made excellent material for mockery:

“What trustworthy witnesses to the death, cremation, and burial! Three freedmen—a concubine and two wet nurses—and a eunuch! How can anyone believe such witnesses? The whole thing is a farce. Though, admittedly, it is very entertaining, as befits a great artist.”

Such and similar gossip was heard among the people now suddenly deprived of the best joys of life: blood games, chariot races, and song-and-dance performances. And also of the joy of gossiping about palace intrigues, crimes, and orgies—there were no such topics with the new emperor, Galba, the octogenarian killjoy.

Oh, for those wonderful times of their beloved Nero!—they were sorely missed. Fresh flowers were often found on the altar in front of the porphyry sarcophagus in the Domitians’ tomb. Often, the flowers were laid by people who claimed the sarcophagus was empty or contained false remains—they still wanted to express their attachment to the memory of their beloved emperor.

In the Forum itself, right next to the main Rostrum, images of Nero appeared at night. And his edicts—edicts in which the still-alive Emperor announced from hiding in a threatening tone: “I will soon return to take revenge on all those who have betrayed me and my people!”

Fate seemed to inspire such hopes: Galba, the man who had overthrown Nero, reigned for barely half a year. On January 15, AD 69, the soldiers of the imperial guard—the Praetorians—murdered him in the Forum. They did this in a coup staged by one of Galba’s earliest supporters, Otho.

This Otho had once been one of Nero’s closest friends. In AD 58, Nero took his beautiful wife, Sabina Poppea, and sent him into honorary exile in Lusitania as governor of that province (today’s Portugal and western Spain). From that distant land on the Atlantic, Otho returned to Rome with the new emperor, Galba. He had helped him come to power, but only in passing, only to start a plot against him at the earliest opportunity. He then bribed the Praetorian Guard to kill Galba and elevate him in his place.

That same month, January 69, a month stained with the blood of Galba, frightening news reached the capital: the armies on the Rhine had rebelled. In the first days of AD 69, they acclaimed as emperor Aulus Vitellius, the heretofore governor of Lower Germania. And so the Empire, deprived of the bliss of Nero’s sweet rule, now faced divine punishment: the worst of all wars: a civil war. Those who claimed that the moment of His return was at hand weren’t entirely preposterous: had Nero been alive, all he had to do was to show himself, and the people would have flocked to him for safety.

And now, in February 69—as bundles of spring flowers—humble violets—were being placed on the altar in the Domitians’ tomb—the news came that Nero had indeed revealed himself in the East—somewhere in Greece or in Asia Minor. Yes, that Nero, our Nero, the true Nero: the same face and posture, the same hairstyle, quite long and loose at the back, and even his eyes were the same: grey and attentive, a little nearsighted. Of course, he played the kithara and sang beautifully. That he revealed himself in the Greek East was fully understandable: after all, he had always declared that he loved the Greeks the most because only they could understand a truly great artist.

From:

Aleksander Krawczuk, Rome and Jerusalem, Mondrala Press, 202

Aleksander's Antiquities

Explore antiquity through Aleksander Krawczuk's captivating lens.

CONTACT

NEWS

a.krawczuk@mondrala.com

+352691210278

© 2025. All rights reserved.