About Our Books

Translating and publishing Alexander Krawczuk is a labor of love for us. Our author has published 40 books. We will translate and publish them all. Our next project will be the Athenian Trilogy:

Pericles and Apamea

The Case of Alcibiades

The Road to Cheronea

About Our Illustrations

We beautify our editions of these books with gorgeous prints from some of the most interesting collectible books ever published.

We think this is in keeping with Aleksander's approach to the writing of history: our illustrations lead us to fascinating illustrators, publishing projects, and historical events always related in some way to the main theme of each book. They are a kind of extended footnote to the text.

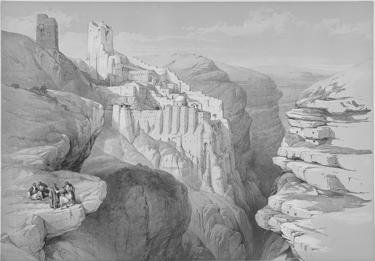

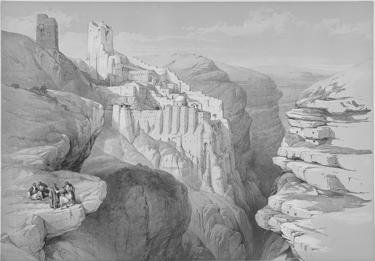

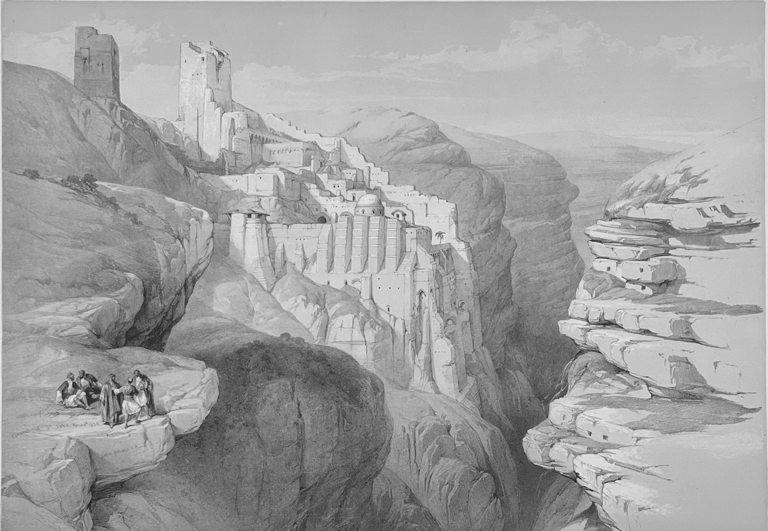

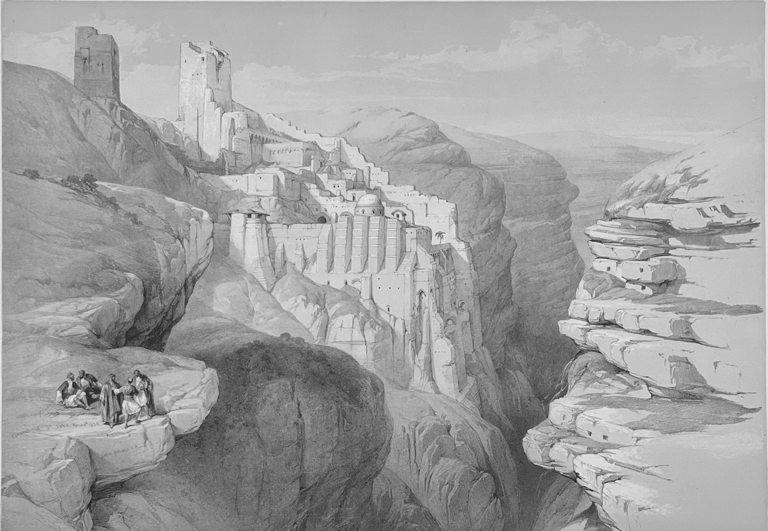

The Illustrations featured in Herod, King of the Jews are taken from “The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia,” a travelogue of 19th-century Palestine and the Middle East, and the magnum opus of the Scottish painter David Roberts. The book contains 250 lithographs by Louis Haghe based on Roberts’s watercolor sketches. It was first published by subscription between 1842 and 1849 as two separate publications: The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, and Arabia, and Egypt and Nubia. William Brockedon and George Croly wrote much of the text, Croly writing the historical, and Brockedon the descriptive portions.

The book has been described as “one of the art-publishing sensations of the mid-Victorian period. It exceeded all other earlier lithographic projects in scale and was one of the most expensive publications of the nineteenth century. It has “proved to be the most pervasive and enduring of the nineteenth-century renderings of the East circulated in the West.” Prints from the series command very high prices — ranging from the high three digits to the low four digits: a very high price for a nineteenth-century print.

The Illustrations featured in Herod, King of the Jews are taken from “The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia,” a travelogue of 19th-century Palestine and the Middle East, and the magnum opus of the Scottish painter David Roberts. The book contains 250 lithographs by Louis Haghe based on Roberts’s watercolor sketches. It was first published by subscription between 1842 and 1849 as two separate publications: The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, and Arabia, and Egypt and Nubia. William Brockedon and George Croly wrote much of the text, Croly writing the historical, and Brockedon the descriptive portions.

The book has been described as “one of the art-publishing sensations of the mid-Victorian period. It exceeded all other earlier lithographic projects in scale and was one of the most expensive publications of the nineteenth century. It has “proved to be the most pervasive and enduring of the nineteenth-century renderings of the East circulated in the West.” Prints from the series command very high prices — ranging from the high three digits to the low four digits: a very high price for a nineteenth-century print.

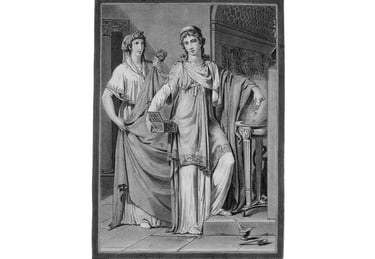

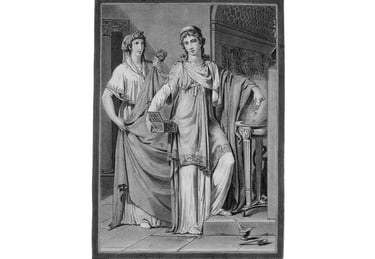

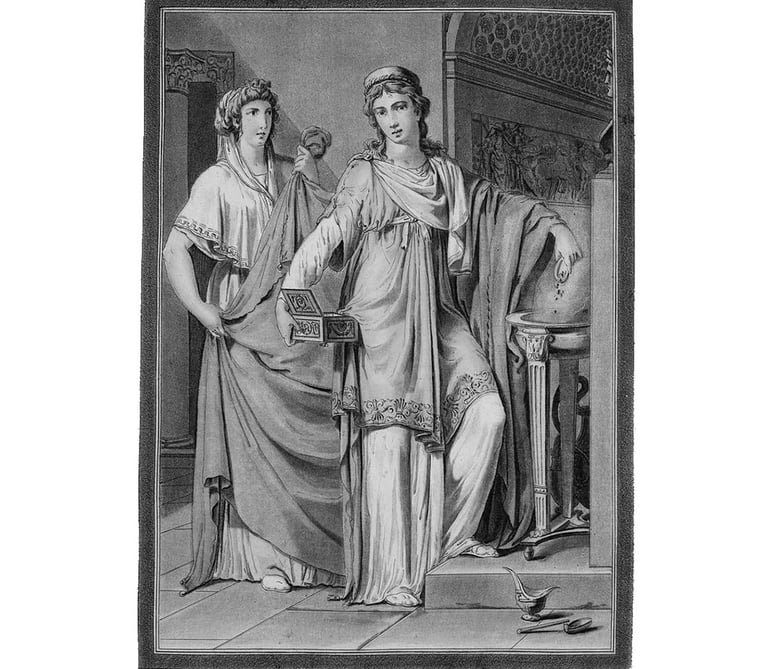

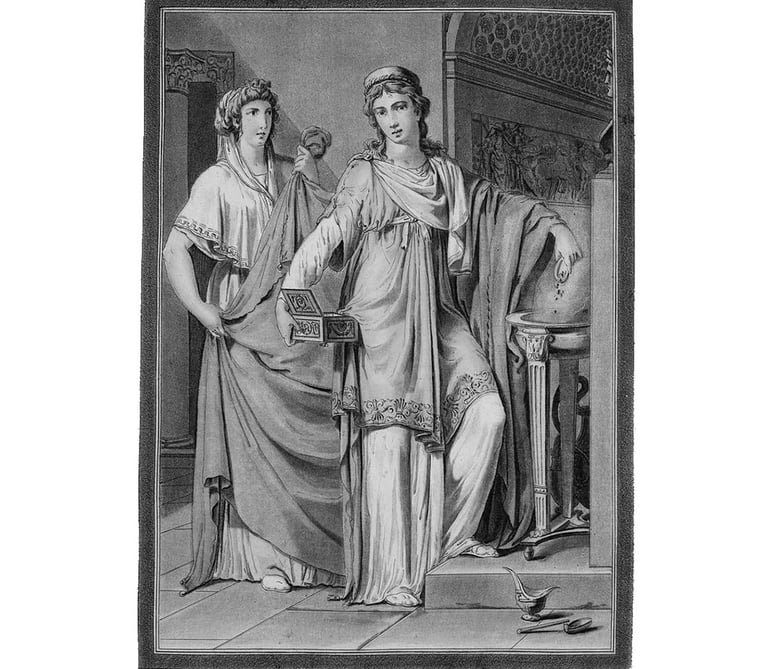

The illustrations to Titus and Berenice are by Philippe Cherry (1759-1833), engraved by Pierre Michel Alix (1762-1817), and taken from the 1802 edition of Recherches sur les Costumes et sur les Théâtres de toutes les nations, tant anciennes que moderns (Research on the Costumes and Theaters of all Nations, Ancient as well as Modern), first published by M. Drouhin, Paris 1790. All refer to Bérénice, the 1670 play by Jean-Baptiste Racine.

The book was written by theater critic and historian Jean Charles Le Vacher de Charnois (1749-92?) and covers classical tragedies and comedies as well as later interpretations of these dramas by playwrights including Racine. Le Vacher de Charnois intended a series of books encompassing, as the title indicates, theatrical costumes from all nations and from the ancient to the modern; however, the French Revolution interrupted his scheme, and as a monarchist, he was imprisoned in 1792 for his writings in support of the aristocracy. It was long thought that he had died in the massacres at the Abbaye prison in September of that year, but later research indicates that he may have been executed during the Reign of Terror in 1794.

The illustrations to Titus and Berenice are by Philippe Cherry (1759-1833), engraved by Pierre Michel Alix (1762-1817), and taken from the 1802 edition of Recherches sur les Costumes et sur les Théâtres de toutes les nations, tant anciennes que moderns (Research on the Costumes and Theaters of all Nations, Ancient as well as Modern), first published by M. Drouhin, Paris 1790. All refer to Bérénice, the 1670 play by Jean-Baptiste Racine.

The book was written by theater critic and historian Jean Charles Le Vacher de Charnois (1749-92?) and covers classical tragedies and comedies as well as later interpretations of these dramas by playwrights including Racine. Le Vacher de Charnois intended a series of books encompassing, as the title indicates, theatrical costumes from all nations and from the ancient to the modern; however, the French Revolution interrupted his scheme, and as a monarchist, he was imprisoned in 1792 for his writings in support of the aristocracy. It was long thought that he had died in the massacres at the Abbaye prison in September of that year, but later research indicates that he may have been executed during the Reign of Terror in 1794.

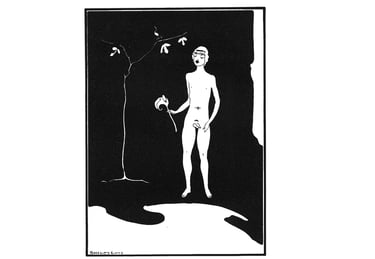

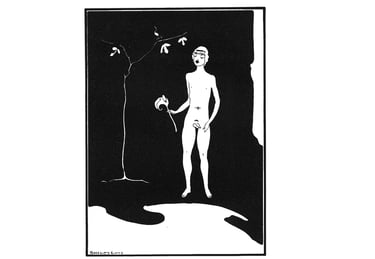

We have illustrated our edition of Seven Against Thebes with the beautiful, evocative illustrations by Adolfo de Carolis created for the 1929 Italian edition of Sophocles' tragedies, translated by Ettore Romagnoli. They showcase De Carolis's Symbolist style with rich detail and dramatic flair, typical of his renowned work for D'Annunzio and his significant murals.

We have illustrated our edition of Seven Against Thebes with the beautiful, evocative illustrations by Adolfo de Carolis created for the 1929 Italian edition of Sophocles' tragedies, translated by Ettore Romagnoli. They showcase De Carolis's Symbolist style with rich detail and dramatic flair, typical of his renowned work for D'Annunzio and his significant murals.

The whimsically delightful illustrations which appear in A Meeting in Oea are by Jean de Bosschère (1878-1953), a Belgian author and illustrator, who illustrated the 1925 Bodley Head limited edition of Apuleius’s Golden Asse.

The whimsically delightful illustrations which appear in A Meeting in Oea are by Jean de Bosschère (1878-1953), a Belgian author and illustrator, who illustrated the 1925 Bodley Head limited edition of Apuleius’s Golden Asse.

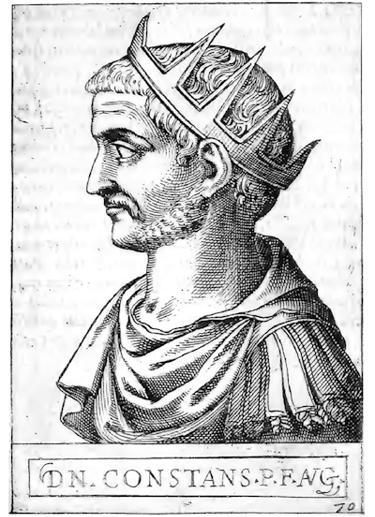

The illustrations featured in The Devil's Brood are taken from Romanorvm imperatorvm effigies: elogijs ex diuersis scriptoribus per Thomam Treteru S. Mariae Transtyberim canonicum collectis, or, Portraits of Roman Emperors: eulogies collected from various authors by Thomas Treter of St. Mary in Trastavere. Tomasz Treter was a son of a Poznań family of book binders, a philologist, translator, and poet with a clerical career in Rome and Poland (where he succeeded to a canonry once held by Copernicus). The book, published in 1583 with entirely fanciful illustrations by Giovanni Battista Cavalieri, was dedicated to Stephen Bathory, King of Poland, with a beautiful frontispiece featuring the Polish coat of arms.

The illustrations featured in The Devil's Brood are taken from Romanorvm imperatorvm effigies: elogijs ex diuersis scriptoribus per Thomam Treteru S. Mariae Transtyberim canonicum collectis, or, Portraits of Roman Emperors: eulogies collected from various authors by Thomas Treter of St. Mary in Trastavere. Tomasz Treter was a son of a Poznań family of book binders, a philologist, translator, and poet with a clerical career in Rome and Poland (where he succeeded to a canonry once held by Copernicus). The book, published in 1583 with entirely fanciful illustrations by Giovanni Battista Cavalieri, was dedicated to Stephen Bathory, King of Poland, with a beautiful frontispiece featuring the Polish coat of arms.

The illustrations in this book are taken from The Eleven Caesars, a series of engravings by hand unknown and published in London by Thomas Bakewell between 1790 and 1799. They themselves were copies of engravings by Aegidius Sadeler II (1570–1629), a Flemish engraver active at the Prague court of Rudolf II. They, in turn, were based on a series of half-length portraits of eleven Roman emperors painted by Titian in 1536-1540 for Federico II, Duke of Mantua.

These eleven imaginary portraits, inspired by the Lives of Caesars of Suetonius, were among Titian’s best-known works. The paintings were housed in a purpose-built room inside the Ducal Palace in Mantua. Bernardino Campi added a twelfth portrait in 1562. Between 1627 and 1628, the paintings were sold to Charles I of England by Vincenzo II Gonzaga in perhaps the single most famous collection acquisition in European history, and when the Royal Collection of Charles I was broken up and sold after his execution by the English Commonwealth, the Eleven Caesars passed in 1651 into the collection of Philip IV of Spain. There, they were all destroyed in a catastrophic fire at the Royal Alcazar of Madrid in 1734 and are now known only from copies and engravings.

The illustrations in this book are taken from The Eleven Caesars, a series of engravings by hand unknown and published in London by Thomas Bakewell between 1790 and 1799. They themselves were copies of engravings by Aegidius Sadeler II (1570–1629), a Flemish engraver active at the Prague court of Rudolf II. They, in turn, were based on a series of half-length portraits of eleven Roman emperors painted by Titian in 1536-1540 for Federico II, Duke of Mantua.

These eleven imaginary portraits, inspired by the Lives of Caesars of Suetonius, were among Titian’s best-known works. The paintings were housed in a purpose-built room inside the Ducal Palace in Mantua. Bernardino Campi added a twelfth portrait in 1562. Between 1627 and 1628, the paintings were sold to Charles I of England by Vincenzo II Gonzaga in perhaps the single most famous collection acquisition in European history, and when the Royal Collection of Charles I was broken up and sold after his execution by the English Commonwealth, the Eleven Caesars passed in 1651 into the collection of Philip IV of Spain. There, they were all destroyed in a catastrophic fire at the Royal Alcazar of Madrid in 1734 and are now known only from copies and engravings.

Or buy a print bundle directly from us.

Free shipping in the US, EK, and EU.

Allow 2 weeks for delivery.

News from Aleksanderland

Aleksander's Antiquities

Explore antiquity through Aleksander Krawczuk's captivating lens.

CONTACT

NEWS

a.krawczuk@mondrala.com

+352691210278

© 2025. All rights reserved.