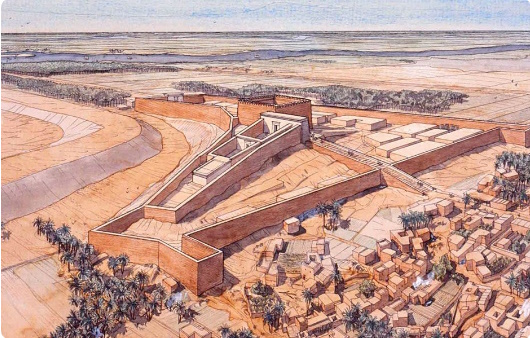

Onias's Temple in Leontopolis. A failed competitor to Jerusalem. llustration by Jean-Claude Golvin, a French archaeologist and architect. He specializes in the history of Roman amphitheaters and has published hundreds of reconstruction drawings of ancient monuments. Golvin is a researcher with the CNRS at the Bordeaux Montaigne University.

Onias's Temple

This other Leontopolis lay on the eastern branch of the Nile. In its chief temple, not one but two lions were worshipped. The lions symbolized the deities Shu and Tefnet, a brother-and-sister pair who were also husband and wife. They were the children of Atum, the great lord of nearby Heliopolis. As a couple, they were commonly referred to as ruti. They piloted the Heavenly Barge of Morning and Evening—that barge with which the souls of the dead had to merge by the use of special prayers in order to soar freely above the mortal earth.

Or that is how things had stood in ancient times, under the old Egyptian pharaohs. In time, the temple fell into disuse, and around 160 BC, the Macedonian King of Egypt, Ptolemy VI, gifted its grounds to a foreigner named Onias.

Onias was a Jew, a descendant of an illustrious family of High Priests. He had fled from Judea when the Syrian king Antiochus, then the ruler of all of Palestine, entrusted the Temple of Jerusalem to another family, one more submissive to his will. Long an enemy of Antiochus, Ptolemy gave a warm welcome to the Judean exile. And the exile, in turn, wishing to repay the king for his hospitality, proposed an extraordinary plan:

Since Antiochus had desecrated the Temple of Jerusalem, it seemed right and proper to erect a new Jewish temple elsewhere, outside of that king’s reach. And why not do it on Egyptian soil? Ptolemy would thereby win over the Jewish opponents of Antiochus: many Jews would leave Palestine and settle on the Nile, where they would be allowed to serve their God in peace and in accordance with the Law.

Ptolemy decided that the plan made political sense and granted to Onias the unused plot of land in Leontopolis. Construction work began immediately, with the support of at least some members of the Jewish diaspora—a diaspora very numerous in Egypt. The temple itself was built in the shape of a tower, 60 cubits high. An altar was set up for the offering of animals, modeled on the altar of Jerusalem. Superb liturgical robes were prepared. Only the seven-branched candlestick that had stood in the Temple of Jerusalem was lacking. In its place, a giant lamp, forged of pure gold, was suspended from the ceiling on a golden chain.

A wall of fired brick surrounded the temple grounds, and stone pylons like those of Egyptian temples framed the gates. The cost of the maintenance of the temple and of the daily offerings was covered by the income of a plot of land graciously granted by the king.

The temple’s location in Leontopolis went against ancient Judean tradition, which held that legitimate sacrifices to the God of the Jews could be made only in one place—in the Temple of Jerusalem on the Temple Mount—and that only houses of prayer (synagogues) could exist outside the holy city. The political claim of Judea aside, many Jews feared that the new center of worship might cause religious division, dilute the sense of Jewish unity, and reduce the revenues of the Temple and of the city of Jerusalem, which they earned from the Jews of the Egyptian diaspora.

As it happened, the hopes of Onias and his king were not fulfilled, and no mass migration from Judea occurred: Judea soon regained full independence, the Temple of Jerusalem was reconsecrated, and it functioned successfully for several decades, well into the Roman period. And yet, the colony of Leontopolis lived on for many generations, and its memory has survived to this day in the Arabic name of the place: Tel-el-Yehudiyeh—Jews’ Hill.

Numerous facts about the settlement are preserved on inscribed tombstones. Today, they are housed in the museums of Cairo, Alexandria, Paris, and Saint Petersburg.

The inscriptions are in Greek, and the names of the deceased are sometimes Greek (Aristobulus, Alexander, Onesimus, Glaukias, Theodora, Arsinoe, Demas, Nicanor, Hilarion, Philip, Dositheus, Nicomedes, Elpis); sometimes Hebrew (James, Joseph, Judas, Samuel, Jesus, Nathan, Onias, Barchias, Rachelis, Joannes, Eleazar (that is to say, Lazarus), Sabbataeus, Sambaios; and sometimes formally Greek, but really Judean: Salamis (Salome), Marin (Mary), Irene (a translation of Salome, meaning Peace).

Here is a typical epitaph from Leontopolis:

“Eleazar, noble and popular, aged thirty. (Died) year Two of Caesar, 20th Mehir”.

By our reckoning, Lazarus died on 14 February 28 BC. (The “Caesar” of the inscription is Octavian, who later became Emperor Augustus).

Another inscription, missing its first line, is more eloquent:

“You, who loved your brothers, who loved your children, who were kind to all, goodbye! May the earth cradle you gently. She died aged about 45. Year 19, which some people reckon as Year 3, the 5th of Pachon.”

This double dating allows us to establish that the woman whose name we do not know died on April 30, 35 BC, during the reign of the infamous Queen Cleopatra VII, the last ruler of independent Egypt, the beloved of Antony.

Several longer inscriptions survive:

“O passerby, cry for me, a mature girl. I lived a blissful life in luxurious chambers. I had my whole trousseau ready for my wedding, but I died prematurely. Instead of a marriage bed, this gloomy grave awaited me. When the clatter of wedding knockers rang out, it announced my death. Like a rose in a garden full of dew, Hades suddenly snatched me away. Passerby, I was only twenty.”

The opening and closing lines of the inscription are versified. Other inscriptions are all in verse:

Passer-by, I am Jesus, son of Phameios.

I descended to Hades at the age of sixty.

Mourn for me, all of you, me, who

Has suddenly departed into the abyss

To dwell hereafter in darkness.

Cry also you, o Dositheus!

You, of all, should shed the most painful tears

For you are now my successor since

I have died without issue. All of you,

Who gather here, weep for unfortunate Jesus!”[1]

[1] J. B. Frey, Corpus Inscriptinum Semiticarum, II 1936, Rome 1936, pp. 37—438, Josephus Flavius, The Jewish War, VII 10, 2.

Aleksander's Antiquities

Explore antiquity through Aleksander Krawczuk's captivating lens.

CONTACT

NEWS

a.krawczuk@mondrala.com

+352691210278

© 2025. All rights reserved.